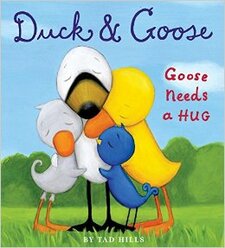

I stopped at the library yesterday to pick up some books I'd reserved. When I did, the librarian asked me if I'd found “Goose Needs a Hug” yet.

When I said it wasn't lost, she responded, “Oh. I just assumed it was since you've had it since July.”

Now, maybe that makes me a bad library patron, but it also means that my 16-month old daughter loves to read and this particular installment of Duck and Goose happens to be one of her favorites.

It's one of mine, too.

The book begins with Goose telling his feathered friends, “I'm feeling sad. I think I need - .”

Immediately, his friends interrupt him and tell Goose what he needs: A game of hide-and-seek, a game of tag, to stand on his head, to splash in puddles, or a happy song.

Each time his friends interrupt, Goose explains that's not what he needs only to be interrupted again, before he can actually tell them what he needs.

Eventually, Goose's friends ask him, “What, Goose?”, at which point, he informs them that what he really needs is a hug.

They oblige and then question, “Why didn't you say so?”

How often, I wonder, are we like Goose's friends?

How often do we assume to know what our spouse or children need?

How often do we assume to know what our friends need?

How often do we assume to know what poor people need?

A few weeks ago, my husband and I were downtown Chicago. It was a hot summer day and we passed a man holding a sign asking for money. A guy darted out of a Dunkin' Donuts and threw a bottle of water at the beggar, who screamed, “Why do I want your half-drunk water?” to which the giver responded, “It's hot man! You might need it later!”

Like the water giver, those with privilege often assume to know what those without need.

As church workers, we often do this with service projects, too.

We see needs our congregation has the resources to meet. So we do – without every dialoguing with the recipients of our charity to see if those resources are welcome. Such acts of service leave us – the privileged givers – feeling good and useful. But what impact do they have on the recipients?

Often recipients are left feeling devalued, unseen, and objectified. Worse still, sometimes our acts of service actually do catastrophic harm to communities, taking away jobs and leadership opportunities from those who reside within it.

What Goose reminds us of in this toddler book is that true helping starts with listening.

The people most equipped to identify a solution to a community's needs are those who have the need and live within the community.

But the only way for us to find that out is to stop assuming we know what people need. In other words, we need to stop talking and start asking questions and truly listening to what people are telling us.

When we do that, we have the opportunity to form partnerships that do good rather than belittle people; that raise up rather than destroy indigenous leaders. When we ask questions and listen, we have the opportunity to form mutually beneficial partnerships with others – partnerships that actually meet the real needs of a community.